Looking Back On 50 Years With “Wish You Were Here”

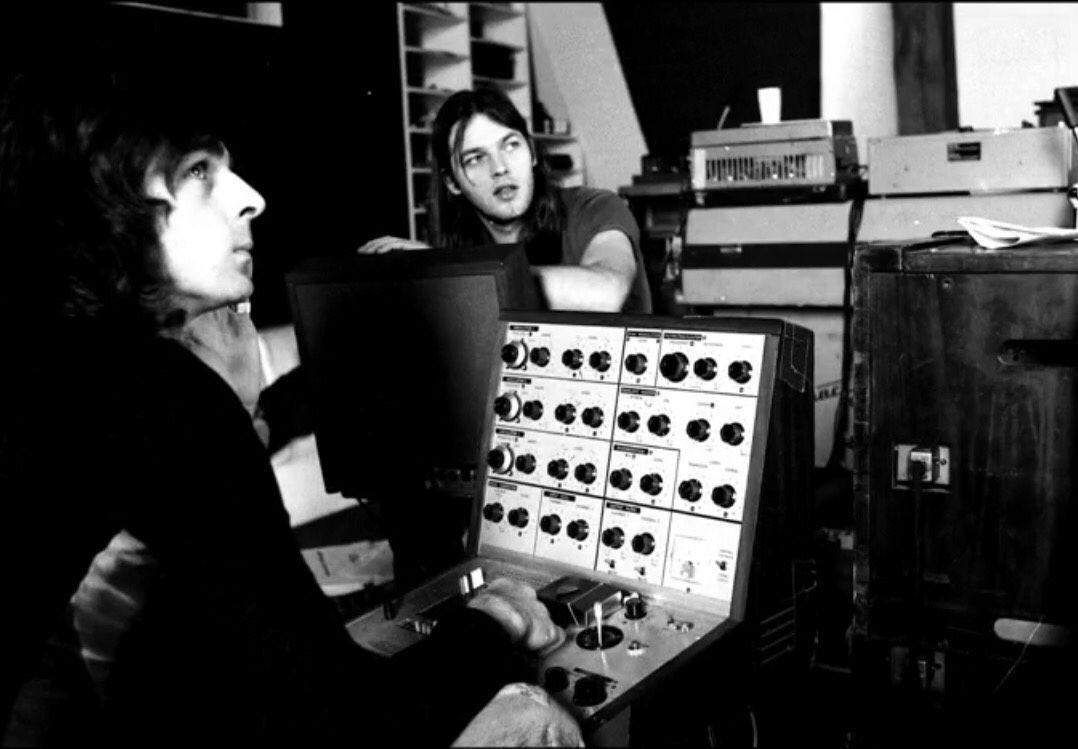

On a cold mid-January day in 1975, a road-weary band began working on a new record in a collectively uncomfortable mood, not much warmer than the London winter. Recording sessions set to take place at the familiar EMI Abbey Road Studio #3, where the band had recorded the bulk of their eight previously released albums. However, these upcoming sessions would occur in a setting that felt impossibly uncomfortable and unfamiliar.

Since their last recording, the studio had undergone a complete refit, which led to some “F-bomb” worthy technical setbacks early on; however, technical setbacks were not the source of the prevailing tension in the studio. Nor did it have anything to do with any personnel changes. Since the departure of the former frontman and primary songwriter in 1968, the band's lineup had remained consistent and flourishing for the past seven years.

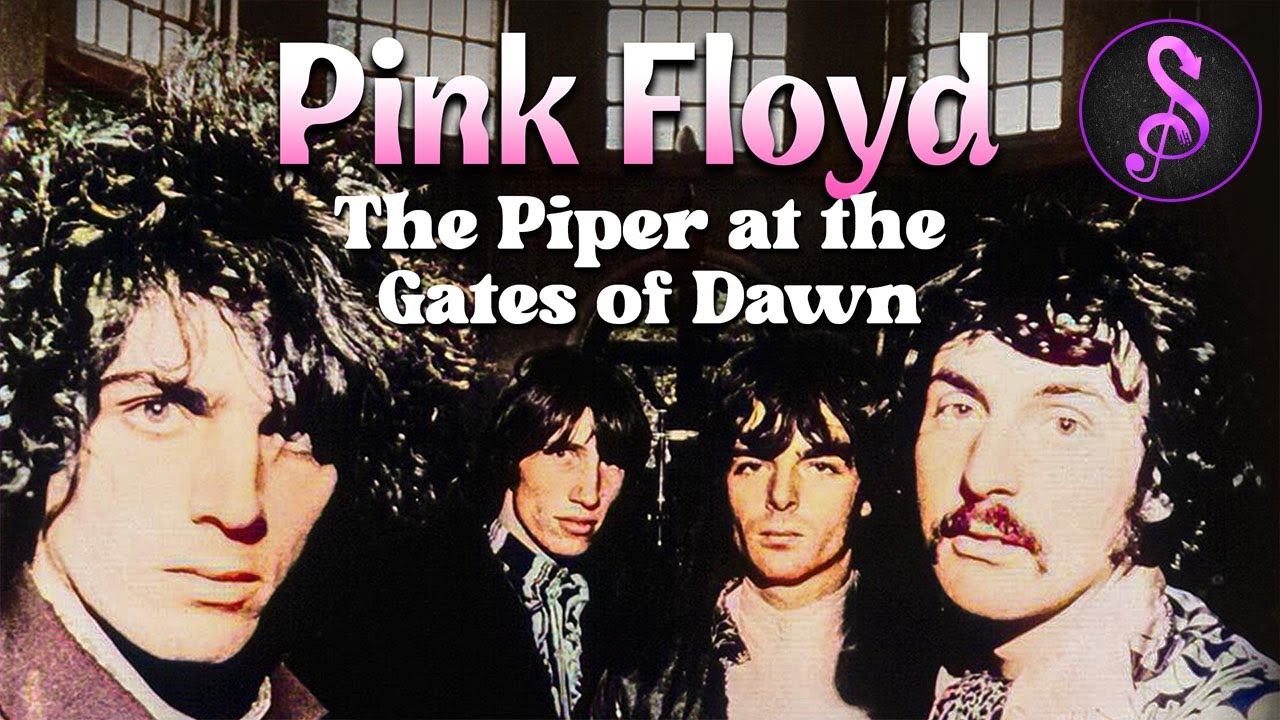

It all started back in 1965, with the name "The Tea Set" (and a few others), before settling on an amalgamation of American blues artists Floyd Council and Pink Anderson. At that time, the band was led by the charismatic but troubled Syd Barrett, whose psychedelic songcraft and electrifying live performances helped them make a name for themselves in the London club scene. By 1967, the band had secured a unique recording contract with EMI/Columbia Records. That band was paid a $5,000 signing advance (equivalent to approximately $40,000 today), which wasn’t a substantial financial gain; however, the contract also provided nearly unlimited access to EMI’s recording facilities. Despite this artistic boon, real money, big-time fame, and fulfillment outside the UK remained elusive until 1973, when the band entered the studio as relative unknowns for the last time. After seven marginally successful albums and years of hard work, “Dark Side of the Moon” propelled Pink Floyd into a massive global phenomenon.

Mentally and physically fatigued, and uncomfortable in their new role as colosseum packing rockstars, the band found themselves in “a bit of an existential crisis.” Having unexpectedly acquired wealth, fame, and musical success beyond their wildest ambitions, what could come next? Roger Waters later lamented, “Dark Side of the Moon was so successful that it was really the end of the road. “We'd reached the point we'd all been aiming for since we were teenagers. There was really nothing more to do. If we could have accepted what we were in it for--we could have all split up gracefully at that point.”

Fortunately for millions of fans, the band pressed on, without taking time to unwind, reflect, or reevaluate. After DSOTM* reset the bar of music industry success, "the machine” was already salivating for its next pound of flesh. The band had little choice but to channel their emotions into a follow-up to the world's bestselling album to date.

*Dark Side of the Moon swiftly became the #1 album of 1973. After an unprecedented 980 weeks (nearly 18 years) in the top 200, DSOTM has sold over 50 million copies to date, becoming the number one album of the 1970s and the 3rd best-selling album of all time.

Over the Moon – And Back Down to Earth

With industry success to back it up, many Pink Floyd fans consider "Dark Side of the Moon" the "greatest album" ever made. With the same breath, the fans (and the band themselves) often refer to "Wish You Were Here" as their "favorite” Pink Floyd album. While that sounds paradoxical, it’s not entirely contradictory. Although they are consecutive releases, Pink Floyd approached each from a fundamentally different perspective, and each was released in a distinct musical era.

Pop/Rock music had already evolved significantly since its emergence in the 50s. New styles and genres emerged, featuring a more ambitious range of instrumentation and greater musical and lyrical complexity. By the mid-60s, hit songs began to exceed the five or six-minute mark, shattering the myth that nothing over two-and-a-half minutes would ever get any radio play. Towards the late sixties, album (LP) sales were on track to outpace 45 RPM singles as the largest segment of a rapidly changing musical landscape and an explosively expanding music industry. While there is no official end to the “singles era”-- or a beginning of the “Album Era,” many consider Pink Floyd’s multi-million-selling “Dark Side of the Moon” as the pivotal moment. It is in this new era of AOR (Album Oriented Rock) that “Wish You Were Here” will arrive.

“Wish You Were Here” hit the shelves in September of 1975—roughly two and a half years after Dark Side of the Moon arrived in March of ’73. While a two-year (or longer) wait between albums is common for today's artists, such a lapse was like an eternity by mid-70s standards. Making matters even more critical, the explosive popularity of DSOTHM drove demand for new material into a frenzy of anticipation among fans and wild speculation from the media. Making matters even more difficult, Pink Floyd had to deal with record company executives who were already counting on the success of another blockbuster album, with little regard for the quality of the content.

The only party not in a rush to get a new album to market was Pink Floyd itself. After the release of Dark Side Of The Moon, Pink Floyd spent the better part of two years touring around the globe, in increasingly larger venues. By the final leg of their American tour, they were playing consecutive sold-out performances in 50,000-plus-seat sports arenas. Both Roger Waters and David Gilmour have been quite vocal about finding the transition from smaller venues with attentive audiences to colosseums packed with rowdy crowds to be uncomfortable, unfulfilling, and even irritating. This wedge between the band and audiences was echoed tenfold towards the music industry bean counters, who now viewed Pink Floyd as their primary cash-cow. The sudden disillusionment, lack of focused direction, and motivation led to an agonizingly slow start that David Waters later described as “laborious and tortured.”

When “Wish You Were Here” got underway, the only part of the project that had any structure at all was the band's work schedule. Pink Floyd had booked time at EMI Studios four days a week for the foreseeable future. Sessions started at 2:30 PM and often went on until the early AM hours. Thanks to Pink Floyd's “unlimited” studio time contract stipulations, one of the few factors Pink Floyd didn’t need to worry about was wasting time in the studio. By all accounts, that’s precisely what they did—at first. In the first few weeks, the band had made very little progress. All attempts at playing together felt cold and mechanical, lacking genuine connection or presence. Completely dry sessions often devolved into giving the studio's pool table a workout, destroying the dart board with a pellet gun, and lots of bickering. After several weeks without progress, the already challenging project only got darker. Despite the band's initial lack of camaraderie, disillusionment, and intense pressure from the music industry, Pink Floyd managed to transform an emotional lump of coal into a diamond.

The Big Idea

The creative lights suddenly came back on when David Waters picked up on a particularly haunting four-note melody improvised by David Gilmour. This particular combination of intervals (Bb, F, G, E) does not belong to any specific chord or key, which gives it a feeling of isolation. When each note is played in sequence, it creates an emotionally jarring sense of unresolved conflict for the listener. When played simultaneously, it creates a disturbing dissonance that classical era composers called “diabolus in musica” (the devil in music) for its disruption of harmony and balance. This powerfully emotive 4-note motif (unofficially known as “Syd’s Theme”) solidified “Shine on You Crazy Diamond” and proved to be the conceptual catalyst for the entire album.

The term “concept album” is a broad generalization that gets applied to a collection of songs unified by a larger theme. The loosest interpretation might include contributions from various artists to a soundtrack. In more strict interpretations, each song is essential to a complete narrative, much as chapters in a book are. Although concept albums are found across all musical genres and eras, they are most closely associated with progressive rock bands of the 70s, in no small part due to Pink Floyd.

Starting with "The Dark Side of the Moon" and continuing through "The Wall" in 1979, Pink Floyd produced four consecutive concept albums, each critically acclaimed and commercially successful. Among these, "Wish You Were Here" arguably best embodies the essence of a concept album. Unlike "DSOTM," which is broader in scope, or "Animals" (1977) and "The Wall," which follow a complete narrative arc, "Wish You Were Here” takes a more thematic approach. It’s also a real-time, sharply focused reflection of the band's currently fractured psyche and emotional state. According to the band's primary lyricist, Roger Waters, trying to make an album “relating to what was going on there and then” was the only way forward. All in all, Wish You Were Here is a profoundly personal outpouring. Yet, its emotionally charged content is communicated in a universally relatable way, giving the album a quality that resonates just as personally to the listener.

Both lyrically and through the musical vehicle that supports it, “Wish You Were Here” conveys feelings of absence, isolation, disillusionment, and even madness — exacerbated by the pressures of a self-serving music industry. On a deeper level, these themes extend to the band's original songwriter, singer, and co-founder, Syd Barrett, whose already fragile mental health was shattered under the weight of it all. Although the band had little contact with Barret after their 1968 debut, “The Piper at the Gates of Dawn.” Given the band's newfound stardom and success, their feelings of loss over their fallen bandmate were undoubtedly intensified.

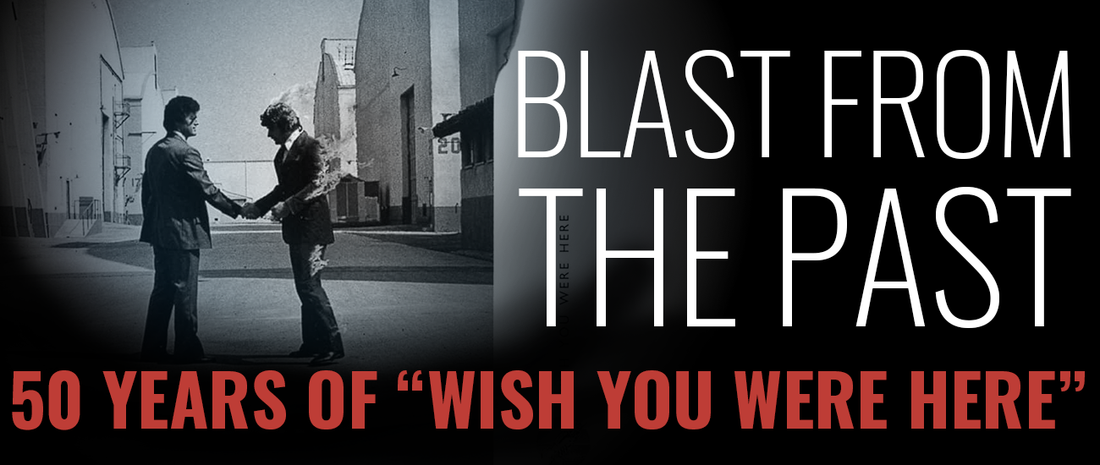

Cold Comfort, Getting burned, Absence, and The Long Goodbye

Compared to other vinyl albums, “Wish You Were Here” falls within the standard running time, at about 45 minutes. Typically, most albums feature about 10-12 songs, each around 3.5 minutes. In stark contrast, "Wish You Were Here" features only four tracks. The album's centerpiece, "Shine On You Crazy Diamond," is split into two halves that bookend the album, totaling nearly 26 minutes. “Welcome to the Machine” is over 7 minutes, plus “Have a Cigar”, and namesake “Wish You Were Here” each run over 5 minutes, leaving the album without any songs of a radio-friendly length. While this impedes the album’s potential to produce hit singles, it reinforces the idea that each song is written to fit within the larger whole.

The length of each song (especially on “Shine”) allows for long instrumental interludes that support the album's lyrical themes. Keyboard player Richard White (with help from Waters and Gilmour) creates ambient harmonic layers and cold, machine-like effects that evoke feelings words can’t quite capture. The emotive, soulful guitar work that made David Gilmour legendary soars over everything in dramatic contrast. On a visual level, the album's mood and thematic concepts are supported by the band's long-term partnership with conceptual artist Storm Thorgerson and his design group, Hipgnosis.

Today's audio recording and digital home studio experts might find it hard to believe that an album with such intricate layers and high fidelity was produced using only 16-track recording technology. “Wish You Were Here” is also the first album recorded at EMI-Abbey Road studio 3, with the new custom-built Rupert Neve console, which replaced the TG12345 “Beatles era” desk. Now, 50 years later, the recording and content quality remain a benchmark.

Starting at a whisper and building to a long crescendo, the sustained opening chord of Shine on You Crazy Diamond sets a dramatically lonely mood. For listeners of today, the sustained chords might sound like an early polyphonic synth. Pink Floyd’s keyboard player, Richard Wright, did have an ARP Solina String Ensemble in time for sessions, but the source of the harmonized drone is something far more organic and clever. The eerie sound was obtained by running a wet finger over the rim of a set of wine glasses, each filled with enough water to create a perfectly tuned 3-note chord. Wright adds the first (albeit synthesized) human element, infusing the drone with melody on his Mini Moog. At the 2-minute mark, the sound of David Gilmour's clean and heavily compressed Strat is heard for the first time, before the drone momentarily stops, to make way for Gilmour’s 4-note “Theme for Syd.” The intro lasts over 4 minutes before the drums of Nick Mason and the Bass of Roger Waters add flesh to the song. Clearly, "Shine on You Crazy Diamond" was written to be a classic, not a hit. Most pop songs have already been through one or two catchy refrain sections within the first minute. On this opening track, Pink Floyd takes every second they need to set the tone, direction, and theme into motion, with instrumental passages only. The listener is left in this solitary, instrumental environment for over 8 minutes before finally hearing a human voice. “Remember when you were young, you shone like the sun?” At first, Waters’ voice and lyrics convey promise and creativity, only to be crushed by pressures, isolation, and fears (both autobiographical and reflecting Syd Barrett's descent into madness). “Now there's a look in your eyes, like black holes in the sky.” In the refrain, a dark kind of acceptance of loss and a tribute to the lost soul—"Come on you target for faraway laughter, come on you stranger, you legend, you martyr, and shine!” After 13 minutes of intensely crafted music and lyrics, the song fades back into the silence it began with.

While “Shine” communicates absence and madness, “Welcome to the Machine” speaks to the cold, inhumane/inhuman source of the symptoms. Written by Roger Waters and sung from “the machines” perspective by David Gilmour, it begins with electronic pulses and sound effects, growing in intensity and layers. In the studio, the futuristic wall of sound that represented the “Machine” environment was imaginatively created by Wright, Waters, and Gilmour, using an EMS VCS-3 portable synth. This early mono synth lacks a keyboard and instead uses a voltage-controlled ribbon, joystick, surface dials, and a patch bay. This makes the synth notoriously tricky to operate, and it's nearly impossible to recreate the same sounds twice. Richard Wright also uses a Hammond Organ, a Solina Orchestrator, and a Minimoog. On this track, Nick Mason used orchestral timpani and percussion, while David Gilmour plays acoustic guitars as a warmer human contrast to the electronic, all-knowing mechanical antagonist. “Where have you been? (without needing an answer) “It's alright, we know where you've been.” Mocking deeper, “What did you dream?”

Specifically reflecting the constructs of life, dangers of success and fame that have made the band feel bitter and hollow, and are a major contributor to Syd Barrett’s downfall. In the end, the Machine only offers a cold, inhuman handshake as a condolence… “Welcome to the Machine.”

From a strictly musical standpoint, the lively tempo, syncopated riffs, standard instrumentation, and arrangement make “Have a Cigar” the album's closest track to a straightforward Rock song. While every song on the album features collaborative efforts, “Cigar” was created by Roger Waters as the sole writer. It's far less abstract, and pointed lyrics are an unveiled jab at greedy, selfish, and demanding elements prevalent within a “soulless” and dirty music industry. Verses include actual remarks made by soulless yes men: “The band is just fantastic, that is really what I think-by the way, which one's pink?” and uncaring bean counters: “You gotta get an album out, We're so happy we can hardly count.” This sentiment is echoed on the album cover, underneath the black shrink wrapper it was presented in. The cold-machine greeting imagery is revisited with two men in business suits shaking hands, leaving one of them “burned.” Ironically (and most likely deliberately), its relatively short 5-minute run time and moderate tempo made it the only suitable candidate for a single.

“Have a Cigar” is the only song on the album to feature a non-band member on lead vocals, for reasons that remain unclear. It's been reported that Roger Waters had a sore throat, and that Gilmour didn’t feel up to it, or refused to sing the lyrics. All we know for sure is that a friend of the band, singer Roy Harper, was recruited to sing the lead vocals on the spur of the moment from an adjoining EMI-Abbey Road studio.

The fade out of the raucous jam at the end of “Have a Cigar” transitions into the title track in one of the most famous and creative segues ever recorded. The song begins with the sound of a person turning the frequency knob on an old-school radio receiver, scrolling through stations. The selected low-fidelity broadcast features a lone acoustic guitarist repeating a sequence of chords until the listener joins the broadcast radio with their own acoustic guitar. Without a single word, this brilliant, immaculate piece of production paints a crystal-clear mental image of two lone souls separated by time, distance, and dimension: The very definition of absence. In the refrain, Waters' lyrics repeat the theme: “We're just two lost souls swimming in a fishbowl year after year. Running over the same old ground, what have you found? Wish you were here.”

This sentiment is directed simultaneously towards Waters’ perceived absence of camaraderie with the band members, beginning with the “Wish You Were Here” sessions. On a more literal level, it's also a mournful lament directed to his old best friend, creative partner, and Floyd co-founder — the now-completely lost from reality, Syd Barrett.

In reflecting on Pink Floyd’s body of work, “The Dark Side of the Moon” clearly marks the end of the band's pre-fame psychedelic era and the beginning of its status as a globally popular musical giant. While “Wish You Were Here” did not equal the commercial achievements of “Dark Side,” it unquestionably cemented Pink Floyd’s ongoing popularity and status as the masters of the concept album. Debuting in the #1 spot, “Wish You Were Here” is Pink Floyd’s fastest-selling release. It went on to become the best-selling album of 1975 and has since become one of the very few albums to sell over 20 million copies. Pink Floyd followed up with two more epic, blockbuster concept albums during the 70s — Animals in '77 and The Wall in '79. Unfortunately, the band members recall “Wish You Were Here” as the beginning of a long goodbye. Stress cracks that formed during the 1975 sessions led to escalating tensions. Over the next 10 years, they intensified like a pressure cooker, culminating in Roger Waters's permanent departure from Pink Floyd in 1985

Pink Floyd in 1967 (L TO R) Syd Barrett, Roger Waters, Richard Wright, and Dave Mason

The Conjuring of Dawn's Lost Piper

While working on the final overdubs and mixing the album's final track, the studio took on an uneasy, electrified atmosphere. Naturally, after such an undertaking, this is to be expected, but events that followed border on the supernatural. Specifically, the album's closing work, “Shine on You Crazy Diamond” (Parts VI-IX), which serves as an elegy for Syd Barrett, delivered some unexpected results.

Details about the actual cause of this nearly ghostly appearance are not entirely clear, but the episode itself remains crystal clear to the bandmates. EMI-Abby Road Studio had a stringent security protocol because the Beatles' sessions drew mobs of fans hoping to get inside. Uninvited, unexpected, and unauthorized visitors were unheard of inside the facility. For that reason, the peculiar man milling about the studio was initially brushed off by the band. He must be another record label “yes” man, studio employee, or at least someone with clearance. The man's strange appearance and odd behavior soon began to feel acutely uneasy. “Who is this guy, and how did he get in here?”

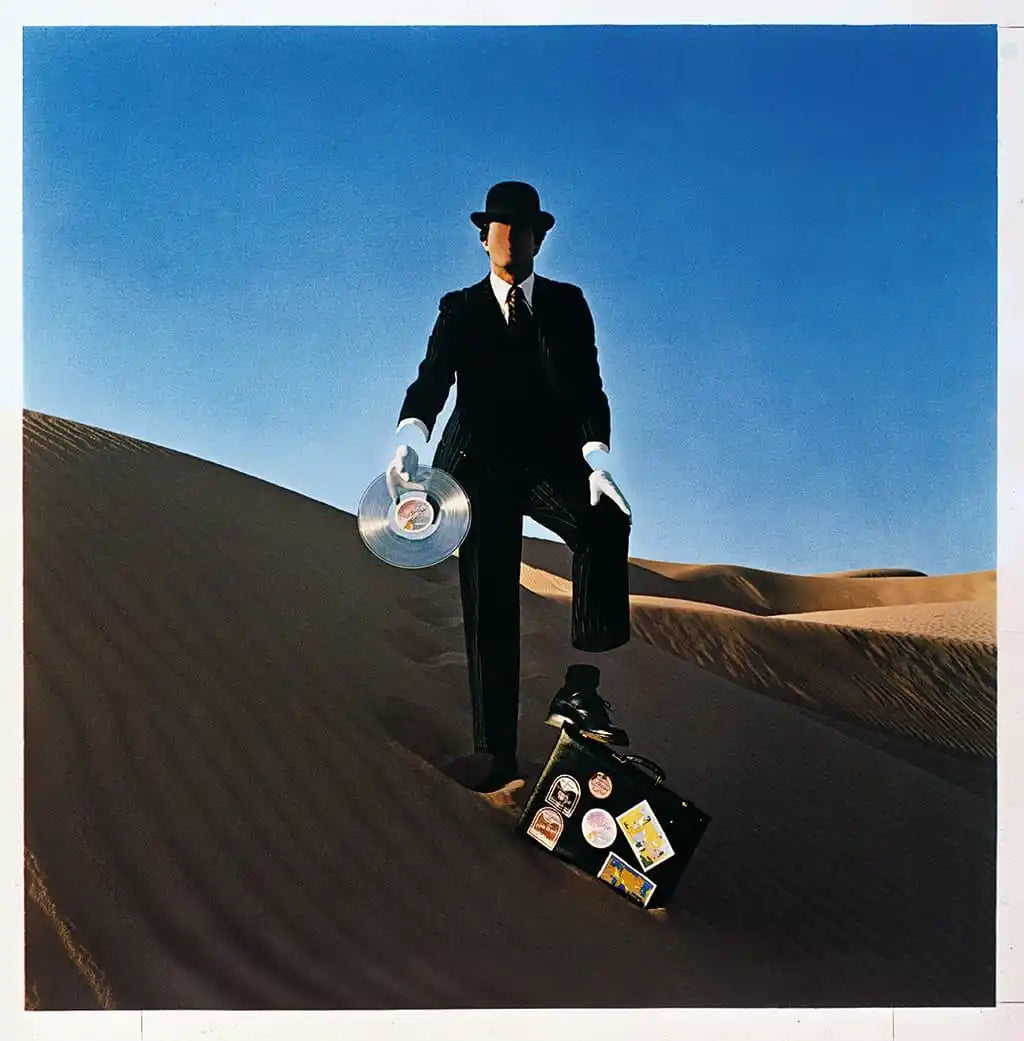

Empty suit, soulless record executive, selling Pink Floyd Music

When David Gilmour eventually recognized the strange visitor, his blood ran cold. The overweight man with a shaved scalp and eyebrows, jumping up and down while desperately clinging to belongings crammed into a plastic bag…was Syd Barrett. After only a few years without seeing their fallen friend, he had become nearly unrecognizable. According to Gilmour, he had to take a long look at Barritt’s eyes before the chilling spark of identification came to him. The entire band went into a state of shock, seeing the recently waif-like, handsome, and charismatic friends decaying physical and mental state. Attempts to communicate with Syd were useless. He spoke in incomplete sentences of mostly gibberish. The experience was reported to be unsettling to the point of tears. After his first random visit, Barrett returned to listen over the next 3 days, as “Shine on You Crazy Diamond was being completed, and never returned. Collectively, or individually, it was the last time Pink Floyd would ever see Syd Barrett again.

The album is a truly melancholy work, yet not without hope. It would be comforting to know that some of that hope, and the realization that he's not alone in his isolation, somehow reached his shattered consciousness.

“Come on, you raver, you seer of visions… Come on, you painter, you piper, you prisoner, and shine!”

Blog posts

View all-

Alto Music Holiday Gift Guide 2025

The Holidays Are Here — and So Are the Best Deals of the Year The holiday season can get hectic—but there’s no need to let the “holiday crunch” become overwhelming. At...

Alto Music Holiday Gift Guide 2025

The Holidays Are Here — and So Are the Best Deals of the Year The holiday season can get hectic—but there’s no need to let the “holiday crunch” become overwhelming. At...

-

Blast From the Past: 50 Years of "Wish You Were...

With industry success to back it up, many Pink Floyd fans consider "Dark Side of the Moon" the "greatest album" ever made. With the same breath, the fans (and the...

Blast From the Past: 50 Years of "Wish You Were...

With industry success to back it up, many Pink Floyd fans consider "Dark Side of the Moon" the "greatest album" ever made. With the same breath, the fans (and the...