2120 South Michigan Avenue

On one sunny June afternoon on Chicago’s south side, back in 1964, Mick Jagger found himself with an uncharacteristic case of jitters. Although it was early on in their career (during the Rolling Stones' first American tour), it’s hard to imagine anything rattling the famously cocky frontman.

The band had arranged to begin recording music for their next single and EP (a 4-song mini-album) at a facility located at 2120 S. Michigan Avenue, in Chicago’s gritty South Side. The sessions were unusual in that the studio had been previously used only by artists signed to the independent record label that owned it. For the Stones, that was the whole point. The Chess Records recording studio offered nothing special technically; in fact, much better studios were readily available to the band. However, the studio did offer something uniquely valuable to the band. Chess Records was the source of the boys' most treasured records, home of their most significant influences, and revered musical heroes. It’s been reported that Mick and Keef's first encounter with each other occurred in a London record shop, seeking singles on the Chess label, to complete their collections. Even the name “Rolling Stones” came from a Muddy Waters lyric. The opportunity to visit and record at the same facility as their idols must have been irresistible.

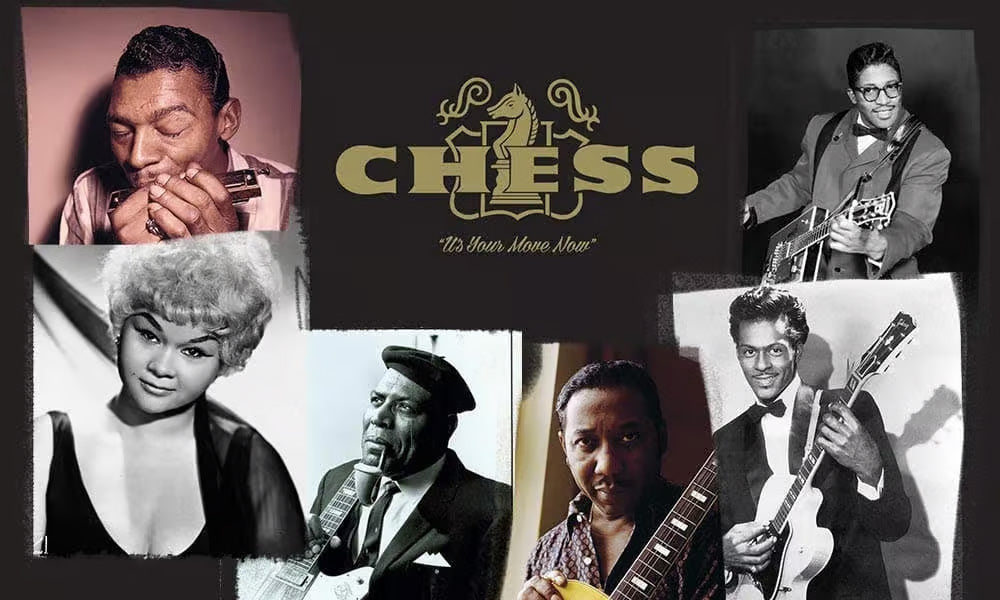

It was Jagger’s job to approach the microphone that had been used to record vocals by Howlin’ Wolf, Bo Diddley, Chuck Berry, Etta James, and a staggering list of Blues and Rock icons—yet nobody expected any of them would be present. With Willy Dixon and Muddy Waters observing from the control room, it’s no wonder Jagger got rattled. The band kicked things off with a Chicago Blues style instrumental tribute to Chess Records called “2120 S. Michigan Avenue” instead of “I can’t be satisfied.” The idea of recording a Muddy Waters cover in front of the man himself ought to be enough to rattle anyone with a pulse.

Despite the Rolling Stones' unparalleled notoriety, even the British Invasion bad boys' pilgrimage to the storied address is merely a footnote in the story of Chess Records. Although the once-bustling studio at 2120 S. Michigan Avenue has long been silent, the protected cultural landmark building continues to serve as a sacred destination for all who wish to visit the cradle of Electric Blues, Rock 'n' roll, and Soul.

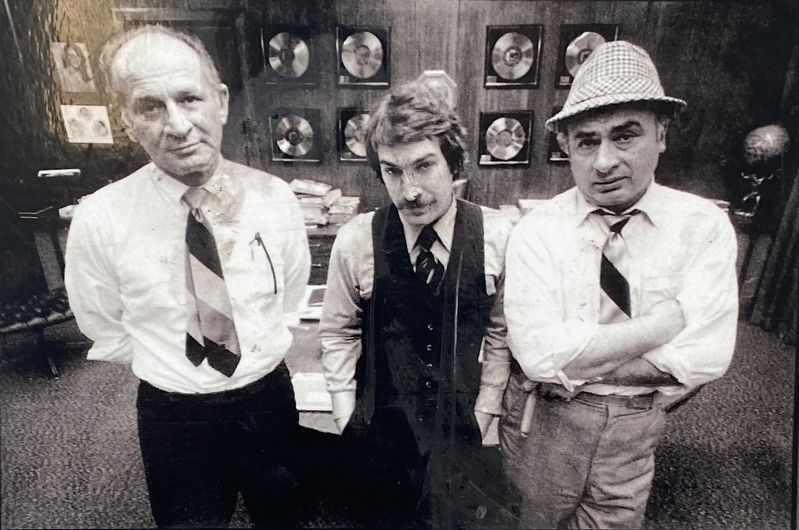

(L to R) Leonard, Marshall, and Phil Chess

The Architects of Chess Records

Along with his mother, sister, and brother, Leonard Chess (originally Czyz) relocated to the USA in the late 1920s. The family of Polish/Jewish immigrants took up residence in Chicago, where their father had already established himself in Chicago’s notorious prohibition-era liquor distribution business. At his father’s side, young Leonard got a bird's-eye view of how (above and below the tables) deals were done, Chicago style. Bright, gutsy, and eager to earn, Leonard developed a bold and fearless knack for calculating risk vs reward, and a drive to grow his fortune with more profitable ventures. These traits made him a natural-born leader and well prepared to answer when opportunity knocks.

Throughout the post-Prohibition 30s and into the early 40s, Leonard and his younger brother Phil remained successful in the liquor business. Without ever needing to expand or risk a dime, the Chess brothers were set up for a comfortable life. However, sitting still and being content was never a part of Leonard Chess’s nature. Come the mid-1940s, Leonard is plotting his next move, and it’s a risky one.

It must have seemed crazy to brother Phil when Leonard pitched the idea to sell off their liquor distribution routes and stores, to buy a run-down South Side restaurant. Phil must have also understood that successfully debating the subject with his driven and ambitious older brother was a waste of time and effort. Just like that, the Chess brothers are in the Nightclub business.

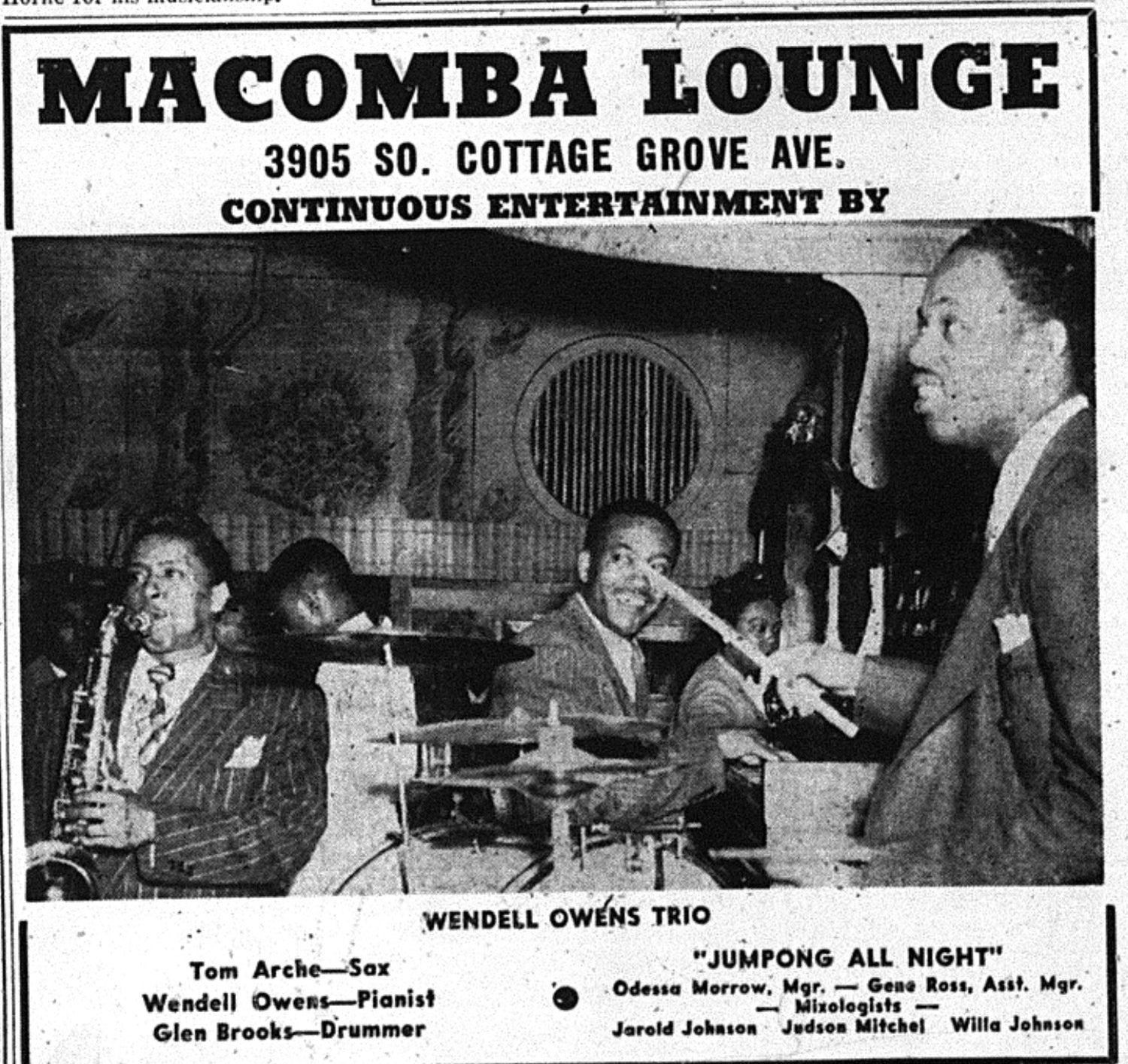

A rare image of the inside of the Chess Brothers' “Macomba Lounge”

After swift renovations, the Chess brothers' nightclub opened for business in 1946. “The Macomba Lounge” catered to the people of the predominantly black South Side neighborhood where it was located. The venue quickly became known for its exceptional live music, packing in huge crowds and drawing in talented local musicians who frequently sat in on jam sessions that would last until the sun came up. It was quickly evident that the Chess brothers' sudden leap into the Nightclub business would be financially successful. However, not even Leonard Chess and his nearly clairvoyant intuition immediately realized the powerhouse that had been put into motion.

Aristocrats to Chess Men

Only a year after the Macomba opened, ever restless Leonard Chess was already seeking ways to expand the brothers' fortune. Investing in additional Nightclubs would have been the safe bet, but Chess followed his instincts and fearless tendency to gamble on a much different idea. Although Chess lacked a musical background, it was clear that the undeniable talent and unique style of the Macomba lounge musicians were the primary factors behind the club's success. Coupled with the nearly constant presence of local talent scouts cherry-picking Macomba lounge band members for session work, Leonard Chess saw an opportunity--and his next big financial gamble.

In those very early days of magnetic tape format recording, very few modern studios were accessible or affordable to locally popular artists. Unfortunately, this was especially true for black musicians of the era, who were seldom featured on mainstream Record labels and Radio programming. As such, the unique style of electrified Delta blues that drove enthusiastic crowds into the Macomba until the wee morning hours was virtually unknown outside of the South Side Chicago ghetto.

After an arranged meeting with the owners of the local independent “Aristocrat Records” label, Chess secured a stake in the company and a position in sales and distribution. This meant weeks on the road, but he established essential contacts, auditioned local talent, and gained a first-hand look at what makes the record business go ‘round.

The Aristocrat label produced mostly Jazz, Dance band, and some Polka music, but nothing at all like the raw and rough-hewn blues played at the club. Chess handpicked Macomba lounge mainstay McKinley Morganfield and his band to record the next Aristocrat single. The results were explosive. Morganfield's first single, I Can’t Be Satisfied, b/w I Feel Like Going Home, shot up to #11 on the R&B charts. That’s quite an accomplishment, especially for a relatively unknown artist, but nothing was left to chance alone. It’s uncanny success like this that shines a light on the way Leonard Chess stacks the odds.

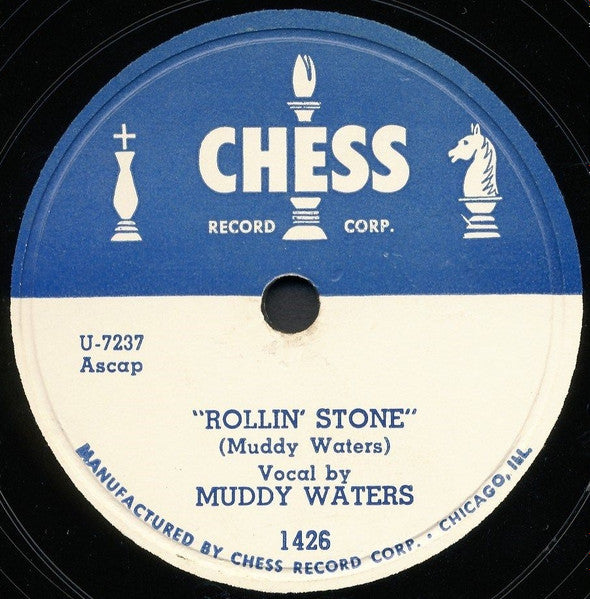

With a bit of help from a $50 bill tucked inside the records' dust cover as a motivational nudge for Radio DJs to include the song on their show, the first pressing of "I Can’t Be Satisfied" sold out in just 12 hours. Although this practice (Payola) is illegal today, it was a legitimate way to “grease the machine” back in 1948--and just one example of how Leonard Chess creatively made things happen. Payouts and other incentives (such as partial writing credit and royalties) were very common in the industry before (and after) 1959, when the practice became illegal. However effective these tactics may have been, they should not be thought of as anything more than a kick-start, and not the reason behind the artist's success. McKinley Morganfield (better known as “Muddy Waters”) and his sound (now known around the world as “Chicago Blues”) speak for themselves.

As successful and gratifying as it must have been for a Macomba Lounge mainstay to score a hit single, nobody could have possibly predicted how influential and far-reaching Muddy Waters and his electrified Delta blues would become. Between 1948 and the end of 1949, Muddy Waters released eight successful singles on Aristocrat, and he was just getting warmed up. Chicago blues exploded in popularity during the 50s, and Muddy was the king of Chicago.

In early 1950, Leonard and Phil Chess bought out their remaining partners, gaining sole ownership of Aristocrat Records. The brothers' next move was to rename the label to help define the new direction and new era. The name “Chess Records” will become practically synonymous with Chicago blues and played a pivotal role in the place and time where R&B, Blues, and Rock ‘n Roll first crossed paths.

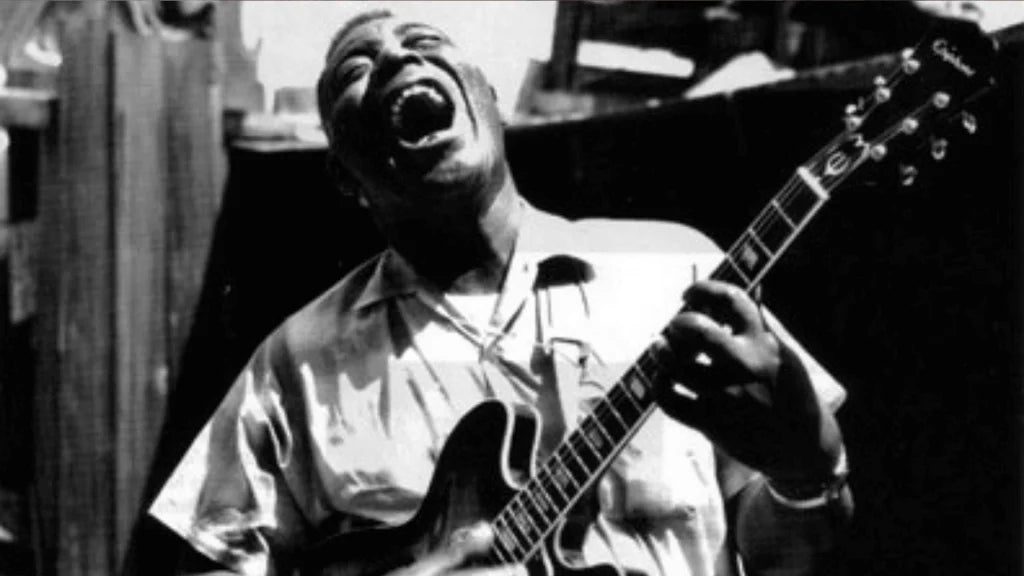

Muddy Waters: The Chicago Blues Revolution.

Muddy Waters was Leonard Chess's first significant musical discovery, yet his first recordings were made a few years before his association with Leonard Chess. Waters' first recordings were captured in 1941 by Library of Congress archivists John and Alan Lomax. This father and son duo traveled to remote rural areas with an early disk recorder to discover, capture, and preserve vanishing styles of American folk music for future generations. On the front porch of the Clarksdale, Mississippi, plantation where he worked and lived, Lomax captured over 60 minutes of Waters performing original songs, and a version of Robert Johnson's “32-20 blues”.

“Chicago Blues” evolved from the traditional country-style blues of the Mississippi Delta, brought to the north by African American musicians during the Great Migration. In the urban environment of Chicago, the style developed a distinct sound characterized by “big beats” and fully electric instrumentation. The lyrics often reflect the modern challenges, opportunities, and even the optimism of living in “Sweet Home Chicago.”

The Chicago-style blues band, pioneered by Muddy Waters and his ensemble, represented a dramatic shift from the soulful yet simple acoustic country blues he initially performed in his hometown of Rolling Fork, Mississippi. With a hard-hitting drummer, electric bass, and a harmonica plugged into an amp to compete with the roaring electric guitars, this new sound retained the same soul-shaking intensity as its Delta blues roots, and more. It balanced this intensity with added power, creating an experience that could not only shake your soul, but also your bones and “money makers.”

During the 1950s alone, Muddy Waters released 44 successful singles on Chess Records, including many of his most popular and influential tracks; Rollin' Stone, Honey-Bee, Rollin' And Tumblin,' Hoochie Cooche Man, Manish Boy, (Got My) Mojo Workin,’ I Just Wanna Make Love To You (and others)—were re-issued for the first (of many) times, in 1958, on Muddy Waters full-length “Album Era” L.P.

Muddy Waters' success opened the floodgates at Chess Records for more African American electric blues pioneers. Despite neither of the Chess brothers having any musical background, they managed to discover and sign some of the most revered and vital artists in American history. As a catalyst for guitar-based R&B and Soul--and the template for up-and-coming Rock ‘n Roll, the 1950s Chess Records roster laid the foundation for a musical revolution.

Howlin’ Wolf

During the Electric/Chicago blues heyday of the 1950s, the Chess brothers managed to wrangle the best musicians, singers, and songwriters Chicago (and beyond) had to offer. While Muddy Waters is generally considered the king of Electric/Chicago blues, he was not alone at the top. With the addition of Chester Burnett (the man known as “The Howlin’ Wolf), Chess Records had two kings of electric blues in their roster, and a fierce rivalry on their hands.

Like Waters, Howlin’ Wolf was heavily influenced by his musical surroundings growing up in the Mississippi Delta area. After spending time in the military, Wolf settled with his relocated family in Memphis during the late 40s. At 6”4 and 275 lbs., Wolf’s stature was nearly as imposing as his forcefully intense, gravelly vocal performance, which got the attention of none other than Ike Turner. Acting as a freelance talent scout, Tuner brought Wolf and his band to meet Sam Philips at the pre-Sun Records era “Memphis recording service.” Philips was so taken aback by the soulful intensity of Wolf’s style that he immediately sent Wolf’s recordings to Leonard Chess for licensing and distribution. Leonard Chess signed Wolf on the spot and convinced him to relocate to Chicago.

Howlin’ Wolf was a good guitarist and blues harp player, but he is known for hiring the best guitar slingers of the era for his band, adding another edge to his sound. Along with his longstanding #1 axe man, Hubert Sumlin, Wolf’s recordings include stellar, highly influential performances by Willie Johnson, Sammy Lewis, Jody Williams, Freddy King, Buddy Guy, and Matt "Guitar" Murphy.

Also like Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf remained a vital and hit-making Chess Records artist from 1951, well into the 60s, as Chicago Blues declined in popularity. With a catalog of classics such as Superstitious, How Many More Years, Smokestack Lightning, Backdoor Man, Sitting On Top Of The World, Spoonful, Little Red Rooster, Killing Floor, and far more, Howlin’ Wolf’s influence is immeasurable.

Among countless awards and accolades, the Bluesman known as “The Howlin’ Wolf” was inducted into the Rock n’ Roll Hall of Fame in 1991

Willy Dixon

Like most of his contemporaries, Willy Dixon is originally from the Mississippi Delta, where he was exposed to blues and gospel music. From a young age, Dixon learned to sing, harmonize, play the guitar, and write lyrics that he’d later adapt into songs. As a 6” 6-inch adult, he was a natural on the standup bass. Perhaps not quite as famous as his fellow artists, or even one of his many classic songs, yet Willy Dixon is one of the most critical figures at Chess Records—and among the most important and influential songwriters in American History.

After a brief stint on Columbia Records, Dixon captured the interest of Leonard Chess after one of his shows at the Macomba lounge. Starting in ’49, Dixon began doing session work for Aristocrat/Chess until he was brought on full-time in 1951. Although Dixon only released six singles on Chess (or its subsidiary) Checkers Records between ’55 and ’62 as the featured artist, he was probably the busiest artist on the roster. In fact, during Chess Records' most prominent era of the 50s to early 60s, Leonard Chess commonly referred to Dixon as “his right hand.”

Dixon’s familiarity with South Side musicians made him an outstanding local talent scout who brought Memphis Slim and others to Chess. His ability to work with musicians on a personal and musical level made him a highly valued co-producer. Dixon also served as the house bassist, playing on nearly every single Chess released in the '50s, making him one of the most recorded bass players of the genre. That’s enough to keep any man busy, but nothing compared to his extremely prolific work as a songwriter and arranger.

During the 50s, Dixon’s compositions became defining classics for Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Bo Diddley, Etta James, Little Walter, Sonny Boy Williamson II, Koko Taylor, and more. His music became highly influential with British invasion bands of the 60s, and beyond. In the 60s, alone, songs from Willy Dixon’s catalog became hits for The Rolling Stones, The Doors, not to mention Led Zeplin’s unauthorized use of his material on their 1st two albums. With over 500 recorded songs to his name (some recorded multiple times by a wildly diverse list of artists, Willy Dixon is the most covered and influential songwriter of all time. For just one example-- a short list of artists that recorded Dixon’s “Hoochie Coochie Man” (mase famous by Muddy Waters in ‘55)-- include Eric Burdon, The Nashville Teens, Dion, The Allman Brothers, Steppenwolf, Chuck Berry, Motörhead, Eric Clapton, Jimi Hendrix, Manfred Mann, New York Dolls, Dave Van Ronk, and Phish. Dixon's songwriting prowess helped define the Chicago blues sound and usher in the era of Rock ‘n' Roll. Looking back, it seems like Mr. Dixon served as Leonard Chess’s right and left hand.

The indispensable Bluesman was inducted into the Rock ‘n Roll Hall of Fame in 1994.

Chess Records and the Dawn of Rock' n’ Roll

On the origins of Rock' n’ Roll, Muddy Waters famously said, “The blues had a baby, and they called it rock and roll." At Alto Music, we also recognize the family resemblance and couldn’t agree more. Just like the blues, you can trace Rock music’s roots with an imaginary line on the map from any point, straight back to the Mississippi Delta. In that way, Chess Records may not be the birthplace of Rock, but it qualifies at the very least as an incubator. One of the first songs to be commonly recognized as Rock ‘n Roll is Ike Turner and Jackie Brenston’s 1951 Chess Records single “Rocket 88.” The song is nearly indistinguishable from the R&B of the era, but the overdriven electric guitar smoking its way out of a beat-up amp, and the car-themed lyrics are a marker of a changing of the guard.

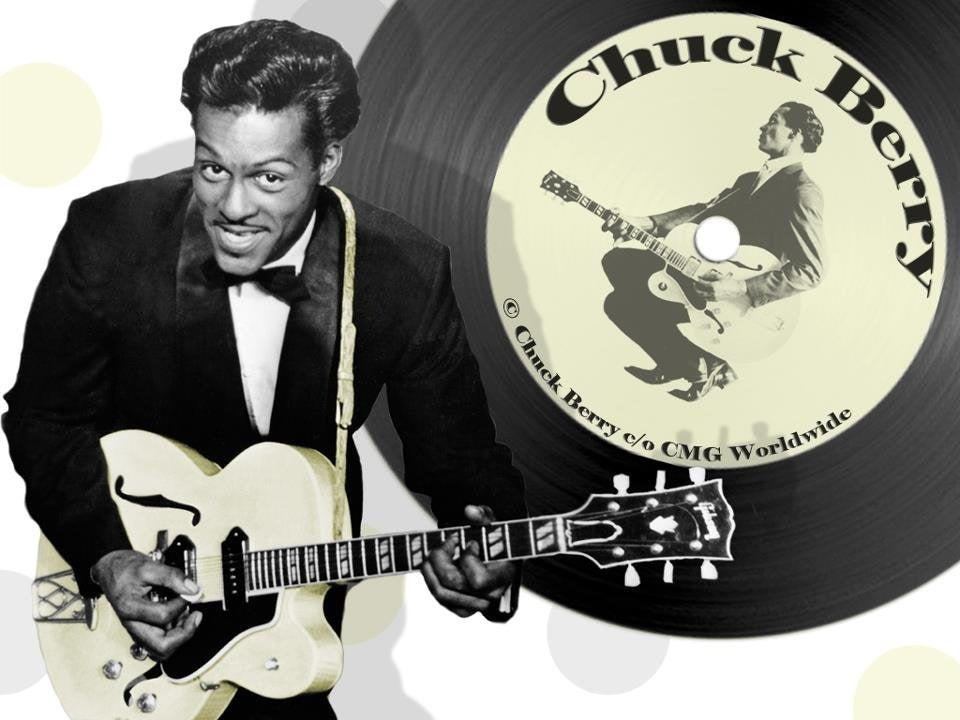

Chuck Berry

As one of the first commercially successful and certainly among the most influential Rockers ever to strap on an electric guitar, Chuck Berry needs no introduction. Chuck Berry and his music are cut from an entirely different cloth than Ike Turner and his Mississippi R&B-infused style. Berry’s upbeat chugging rhythms sometimes borrow as much from Country Music as R&B. His lyrical style was far more lighthearted and relatable to 50s American teen culture than the deep blues of Willy Dixon. Berry’s guitar playing was also from out of left field compared to his fellow Chess Records musicians. His explosive double-stop riffs were more reminiscent of Louis Jordan's big band swing and jump blues than the soulful slide work of Muddy Waters-- or the ripping attack of Wolf’s number one axe man, Hubert Sumlin.

Muddy Waters discovered Chuck Berry in his native St. Louis and was impressed enough to arrange an audition with Leonard Chess and Willie Dixon. Berry played his version of “Ida Red,” which was based on a traditional country song made famous by Bob Wills and the Texas Playboys. Chess loved the music and style, but requested the title be changed to the more relatable “Maybelline,” and immediately signed Berry. The crossover hit and classic pioneering Rock ‘n Roll single hit the airwaves in July of ’55, a year before anyone outside Memphis ever heard of Elvis Presley. In short order, Berry followed up with a consecutive run of 10 nationally charting songs, including Roll Over Beethoven, You Can't Catch Me, Johnny B. Goode, Rock' n’ Roll Music, and more-- making him Rock music’s first guitar hero, and an international star.

Among countless accolades, Chuck Berry was inducted into the Rock ‘n Roll Hall of Fame at the first ceremony in 1986-- and along with composer J.S. Bach, his music is etched in the Voyager spacecraft's golden disk, representing the sounds of Earth.

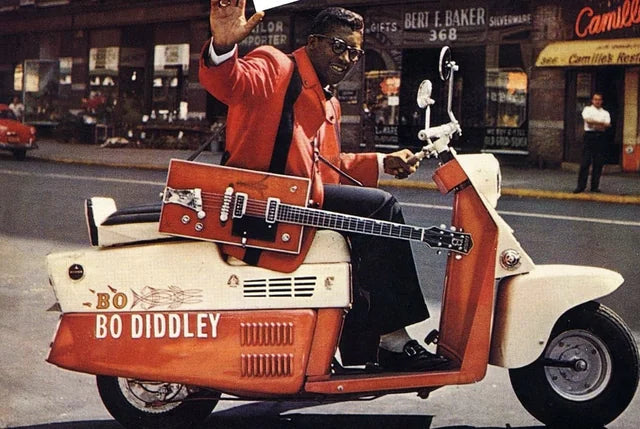

Bo Diddley

Hot on the heels of Chuck Berry, Chess Records had another Rocker ready to go. In late ’55, Bo Diddley (aka Ellas Bates) unleashed his mesmerizing beat on an unsuspecting world, becoming Chess Records' next Rock Star. Like most of the other musicians at Chess Records, Bo is originally from the Mississippi Delta area. His songs are far less polished and far more fierce than Chuck Berry’s brand of Rock ‘n Roll, which is very much a reflection of his Delta blues roots.

His first single Bo Diddley b/w I'm A Man was an instant hit that became more influential than most artists' entire bodies of work. The syncopated “Bo Diddley Beat” (found on the A side) is driving and primal, delivered on Diddly’s overdriven, tremolo-addled guitar, only heightening the simple beat's hypnotic powers. On the “B-side, I’m a Man’s opening 5-note guitar riff that is echoed by harmonica has become so iconic enough to have become commonly used for ringtones on today's cell phones.

The Bo Diddley beat is (while delivered with a bit less intensity) recognizable on hits over the years. A short list included Buddy Holly’s “Not Fade Away, George Michael's “Faith,” U2’s “Desire,” and Tom Petty’s “American Girl.” The magical 5-note Riff from “I’m A Man” is recognizable in Bowie’s “Gene Genie,” George Thorogood’s “Bad to the Bone” (Diddley even appears in the music video), Joe Walsh’s “Rocky Mountain Way,” and even adapted in Koko Taylor's “I’m a Woman.”

Bo Diddley was inducted into the Rock ‘n Roll Hall of Fame the year after Chuck Berry, in 1987.

The Chess Brothers

The Chess Records Legacy

Driven by Leonard’s incredible determination to succeed, Chess Records was in a constant state of change. In 1957, the brothers invested in a dedicated recording studio, offering greater flexibility and access for its artists, while keeping costs down. The company's small infrastructure allowed the label to remain nimble enough to stay at the spearhead of changing musical tastes.

As the 50s drew to a close, Chess Records already had a stable of Rock ‘n Roll artists, who began usurping the popularity of the Chicago Blues sound. By the early 60s, only Chess’s most popular bluesman remade on the label. Chess began branching out into the new style R&B sound and up-and-coming “Soul” music with a new generation of stars, like Koko Taylor and the formidable Etta James. To drive momentum and further popularity for their artists, the Chess brothers spent $1 million to buy a local Chicago AM Radio station. The format/programming was changed to Soul, R&B, and the call tag was updated to reflect its audience. In 1963, WVON (The Voice of the Negro) went live. Later that year, the L&P corps. (Leonard and Phil) also acquired WSDM, to simulcast the WVON format on FM Radio.

Radio was a big step, and a considerable risk, but nothing compared to the future Leonard Chess had planned. In February of 1969, the Chess Brothers sold Chess Records to buy a television station to promote their artists. Unfortunately, it never came to be. Leonard Chess died suddenly and unexpectedly of a heart attack just 6 months after the sale of Chess Records.

Attempting to illustrate the complete cultural impact, or cite (even an abbreviated) list of players that made Chess Records a revolutionary worldwide phenomenon, is far too much to encapsulate in one place. However, the most essential part of the Chess story is easy to summarize. Chess Records was instrumental in overcoming racial obstacles and played a significant role in introducing black music to white audiences, bridging the two cultures in the form of great original American Music.

Blog posts

View all-

Alto Music Holiday Gift Guide 2025

The Holidays Are Here — and So Are the Best Deals of the Year The holiday season can get hectic—but there’s no need to let the “holiday crunch” become overwhelming. At...

Alto Music Holiday Gift Guide 2025

The Holidays Are Here — and So Are the Best Deals of the Year The holiday season can get hectic—but there’s no need to let the “holiday crunch” become overwhelming. At...

-

Blast From the Past: 50 Years of "Wish You Were...

With industry success to back it up, many Pink Floyd fans consider "Dark Side of the Moon" the "greatest album" ever made. With the same breath, the fans (and the...

Blast From the Past: 50 Years of "Wish You Were...

With industry success to back it up, many Pink Floyd fans consider "Dark Side of the Moon" the "greatest album" ever made. With the same breath, the fans (and the...