NYC’s Tin Pan Alley and Brill Building: American Song in the Industrial Age

In today's high-tech era, things change so rapidly that returning to the “pre-smartphone” world we left behind only about 15 years ago is nearly unfathomable. That said, it'd be nearly impossible today to fully grasp the whirlwind of changes happening in the early 20th century, as the Industrial Revolution laid the foundation of our modern world.

Producing Industrial Era commodities required skilled labor, a centralized workforce, factories, significant capital, and effective management. These elements transformed remarkable advancements into everyday realities in our lives and homes. More than any other achievements of the era, the factories, labor, and infrastructure that support them are the foundation of the industry that built the United States. However, what is a nation without a shared musical and artistic identity?

The power of music is undeniable. Whether lyrical or instrumental, music can elevate our moods, move us to tears, inspire us to dance, or encourage action. Music reflects the triumphs and tragedies, patriotism and protest, religious and secular celebration, evolution, and especially the shared identity of its people.

In the decades leading up to the 20th century, the undeniable power of music and the might of the Industrial Age's means of production collided for the first time in history, and nothing will ever be the same.

The Origins of Popular American Music (1700-1880)

Much of the earliest popular American songs and music arrived from England with the colonists. Probably the best example is our national anthem. Like many other well-known "Americanized" songs, The Star-Spangled Banner melody was taken note for note from a popular English tavern song called "Anacreon in Heaven," with new lyrics written by Francis Scott Key. One of the oldest and most famous examples of a borrowed melody is “Yankee Doodle.” The melody is simple, easy to sing, and memorable. More than anything else, this simple method of creating “new” songs for American consumption required only learning new lyrics.

During the Civil War era (1861-1865), troops from all over the US intermingled, sharing, spreading, and building upon their own regionally popular musical styles, influences, and instruments. Wartime compositions like Dixie, The Battle Hymn of the Republic, and marches by John Philip Sousa became the first wildly popular patriotic music of entirely American origin.

Meanwhile, authentic American musical styles began to evolve in rural areas and urban centers, with roots in the musical traditions brought over by our growing multiethnic population. Orchestral music and folk styles from Eastern and Western Europe, call-and-response vocalizing, syncopated rhythms, dances, and instruments from Western Africa (amongst many other styles and places) flourished regionally. Commonly used instruments include European orchestral instruments (especially in professional settings).

In less formal settings and for local enjoyment, the accordion, flute, mouth organ (harmonica), and pre-modern guitar-era stringed instruments like the zither, dulcimer, and Mistral banjo (the African predecessor of the modern banjo) were the most commonly used instruments. However, by the late 1800s, one instrument eclipsed all others in popularity and demand. Thanks to modern industry, the now far more affordable upright piano rapidly became as common in the typical household parlor as a modern stove was in the kitchen. Piano sales grew five times faster than the population, and 8 out of 10 American students enrolled in music reading programs. At the turn of the century, over one million pianos were estimated to exist across America, from the industrial east to the western frontier.

The piano’s range and adaptability to any style of music make it an excellent choice for solo performance, music for dancing, vocal or instrumental accompaniment, and more. In this era before recorded music—or even the radio became available—it's no wonder that its entertainment value was so significant. Of course, this begs the question: what kind of music do people want to hear and play, and where will it all come from?

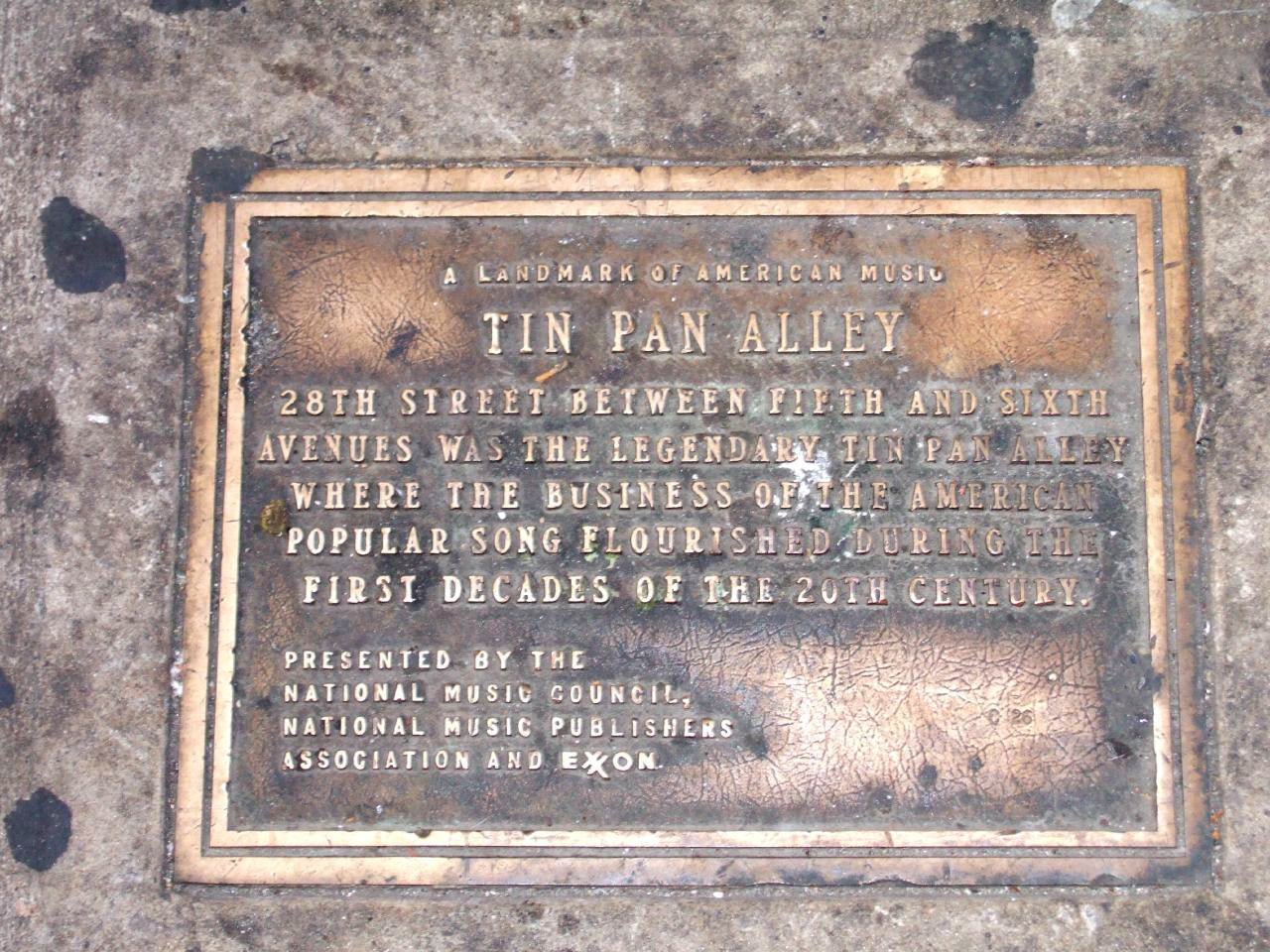

The answer will forever transform how “popular” music is created and distributed, as Industrial Age production collides with America's diverse musical landscape. Believe it or not, the most popular songs, melodies, and standards—literally, the coast-to-coast soundtrack of early 20th-century American life—originated in a one-block-long concentration of music-related businesses in NYC, known today as “Tin Pan Alley.”

“Tin Pan Alley” circa 1910

“Tin Pan Alley”

At its peak in the early 20th century, Tin Pan Alley’s thriving music-related collective of music-related businesses and workshops straddled both sides of Manhattan's 28th Street, between 5th and 6th Avenue, with one purpose: selling popular songs in the form of sheet music. The unofficial origin of the Tin Pan Alley era is generally cited as the arrival of music publishers M. Witmark and Sons on 28th Street in the early 1880s. While most music publishers concentrated on 14th Street and lacked the foresight to publish much more common religious hymns, light classical music, and method books, Witmark and Sons had a fresh idea. As the 1st publishers to concentrate on providing easy-to-learn, popular songs for the booming home piano market, their business model proved extraordinarily timely and massively successful. Naturally, others soon followed suit. Established and upstart music publishers began flocking to 28th Street, swiftly growing into a loosely connected collective and source of popular music.

To begin with, copyright and publishing laws of the time did little to protect songwriters or publishers. Any briskly selling song could be copied and sold by anyone who desired to cash in, without permission or paying royalties. This led to the founding of ASCAP (The American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers) as a safeguard that protected both the songwriters and the publishing companies that promoted and distributed popular songs.

At first, popular songs from NYC’s bustling minstrel shows and vaudevillian musical theater productions became the primary source of “pop” songs published on 28th Street. Already a city of over a million residents, NYC’s melting pot of cultural musical traditions gave birth to a blending of regionally popular ethnic styles—the organic de facto origins of uniquely American music. Soon, demand for popular show tunes grew faster than the theater district could turn them out. In response, most major 28th St. publishing companies began to employ songwriters, lyricists, arrangers, musicians, scribes, and salespeople/promoters known as “song pluggers” to help popularize and sell new songs.

By the turn of the century, every 5-story building on the block was buzzing with activity, and the din of hundreds of songwriters attempting to clang out the next big hit on as many cheap upright pianos crammed into tight quarters. The sound has been described as a million tin pans struck simultaneously, earning the then songwriting capital of the world the handle “Tin Pan Alley” forevermore.

Happy Days Are Here Again Sheet Music

The American Song and the Business Behind It.

The advantage of having so much talent and the means of industry packed in such tight quarters is the speed and efficiency with which business can be done (and money made). When a publisher wanted something for a current event, such as the song “Lucky Lindy” (celebrating Charles Lindbergh’s transatlantic flight), he could give the assignment out to a huge talent pool of songwriters within shouting distance. Songwriters could create a song, get an arranger to enhance it, draft a lead sheet, and sell it to a publisher—all on the same day and the same block. Simply put, Tin Pan Alley was an industrial age “musical factory.”

The first massive money-making song published by Tin Pan Alley was “After the Ball,” by Chas Harris. Whether or not you're familiar with the tune today makes little difference. It’s the song's massive impact that clearly defined the gold mine-like potential of music on an industrial scale. The sentimental ballad was Tin Pan Alley's first “blockbuster,” and quite literally, the first hit song ever written. Within the first year, sheet music for “After the Ball” sold an astounding 5 million units. For perspective, that’s 5X Platinum sales by today's standards.

While we celebrate the enduring melodies and brilliant composers of Tin Pan Alley, 28th Street represents much more than just a talented collective of diverse songwriters. With popular music centrally monetized for the first time in history, it was the publishing houses of Tin Pan Alley that managed and controlled everything. Although thousands of briefly popular, soon-to-be-forgotten “trendy” hits such as “My Merry Oldsmobile” and “Come Josephine in My Flying Machine” were churned out between the 1880s and 1930s, Tin Pan Alley was far more than a “grind house” of disposable pulp music. Some of the most gifted song crafters of the day and some of the world's favorite and most familiar songs and melodies are products of Tin Pan Alley, the music industry’s birthplace.

Although most Tin Pan Alley era music pre-dates recorded music, the songs and melodies have proven too good to be forgotten. Simple, catchy songs like “Happy Days Are Here Again,” "By the Light of the Silvery Moon,” "Give My Regards to Broadway," and "Sweet Georgia Brown" are among Tin Pan Alley’s far-too-many-to-list songs that have worked their way into America’s collective experience.

Songs of American patriotism, such as the WWI call to arms, “Over There,” continue to entertain and inspire. “God Bless America” (our “secondary” national anthem) is a celebration of America's beauty that’s still sung by school-age children and adults with equal reverence. "Take Me Out to the Ball Game" and “You Gotta Be a Football Hero" celebrate our national pastimes. "Hello Ma Baby (Hello Ma Ragtime Gal)” and "Alexander's Ragtime Band" integrated new styles and new slang, delighting musicians and audiences across the nation. Many Tin Pan Alley songs found new life in the recording age, transcending genre. For example, “Ain’t She Sweet” has been recorded numerous times over the years by a diverse list of luminaries that include Tommy Dorsey, Frank Sinatra, Gene Vincent, and even the Beatles. Some readers may be surprised to know that Hank Williams' 1949 number 1 hit and signature song, “Lovesick Blues,” was composed in 1922 by Tin Pan Alley mainstays Irving Mills and Cliff Friend.

Tin Pan Alley helped popularize and integrate music of Polynesia (particularly instruments like the ukulele and steel guitar), blues, ragtime, early jazz, and more. It’s also the strongest force behind the rise to prominence in mainstream music of Jewish and African American musical traditions. It’s also the vehicle that shined the spotlight on brilliant composers such as Irving Berlin, Harold Arlen, Duke Ellington, George Gershwin, Cole Porter, Noble Sissle, and more, enriching and blending American musical styles.

Most music historians cite the end of the Tin Pan Alley era around 1935. Today, all that remains of the noisy and bustling location are a few of the old buildings and a commemorative bronze plaque. However, in influence, method, and effect, it’s still alive and well—it's simply evolved with the industry around it.

It is becoming increasingly difficult to decide where jazz starts or where it stops, where Tin Pan Alley beings and jazz ends, or even where the borderline lies between classical music and jazz. I feel there is no boundary line.

-Duke Ellington

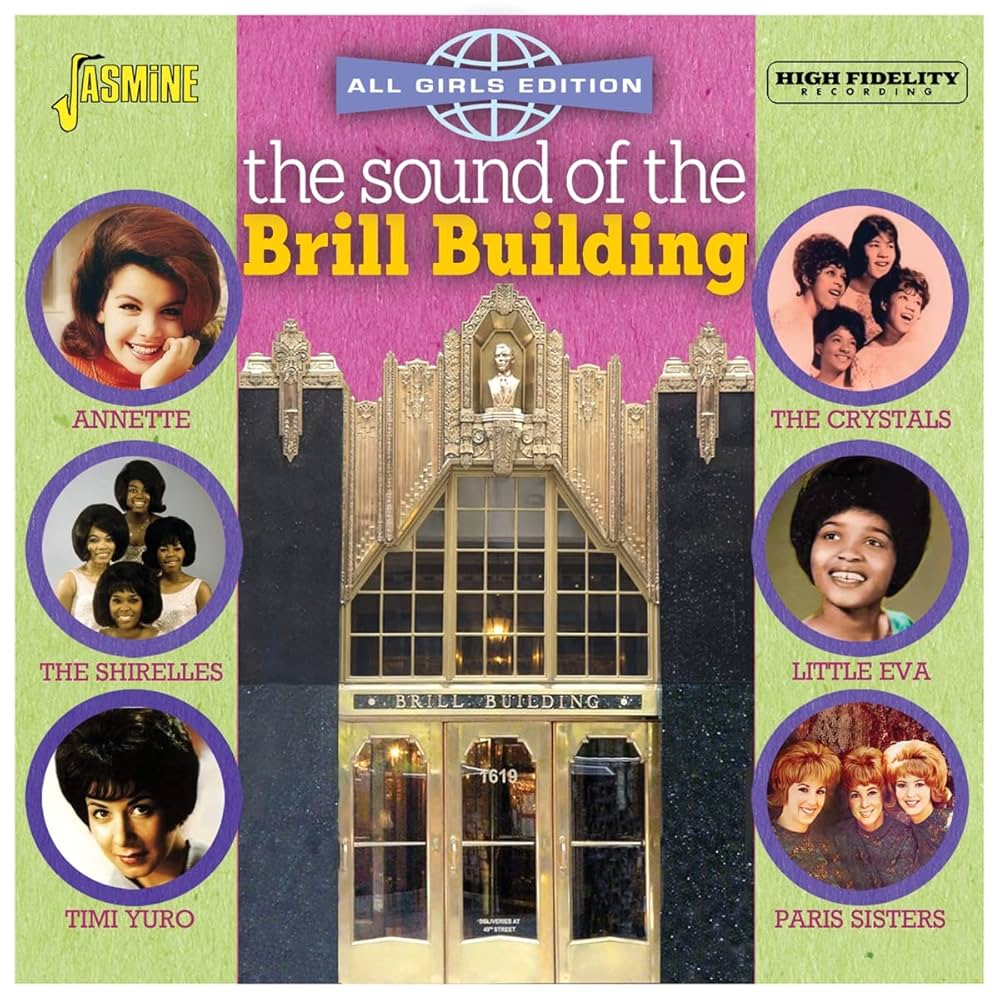

“The Brill Building”

The Brill Building was completed in 1930, just as the Great Depression clamped down on the industrial-age world. What was originally intended as luxurious modern offices had to be subdivided into smaller spaces at reduced rent to attract tenants. The 169 Broadway address (close to NYC’s theaters and music halls) and the low rent attracted many of NYC’s Tin Pan Alley-era publishers and songwriters, plus a new generation eager to revitalize or begin their careers. By the mid-50s, the Brill Building hosted over 160 music-related businesses.

Structurally, NYC’s Brill Building musical collective operated much the same way as Tin Pan Alley. A concentrated group of songwriters, publishers, arrangers, and musicians all working in one concentrated collective, with one major industrial age difference. While Tin Pan Alley (with help from the song plugger) sold sheet music in the age of parlor music, the Brill Building (with help from recording producers) and artists that brought them to life, the Brill Building sold recordings in the age of magnetic tape, the phonograph, radio, jukebox…and rock n’ roll.

Rock and roll developed organically from delta blues and rhythm and blues, pioneered by artists like Sister Rosetta Tharpe with “Strange Things Happening Every Day" in ’44, "Good Rockin' Tonight" by Wynonie Harris (1948), and more. The typical instrumentation featured piano, drums, and vocals, sometimes horns, and the addition of the Fender bass and electric guitar. A perfect example is the gritty guitar riff that literally “drives” Ike Turner’s 1951 classic, “Rocket 88.” This DIY songwriter and artist package shares similarities with the big band and swing era, highlighting the importance of the artist's input.

The Brill Building model signifies a return to the operational style of the music industry seen in Tin Pan Alley. In this model, authority and power have shifted back to the publishers and record labels, resulting in performing artists or bands with minimal input regarding song selection, style, or arrangement. This comprehensive assembly line methodology, refined production processes, and exceptional song crafting generated numerous hits between the late 1950s and 1960s, defining “the Brill Building sound.”

The Brill Building and songwriting collaborators read like a who’s who of classic pop/rock hitmakers. Although the music is aimed at the teen market and lacks the edge you’d expect from a Bo Diddley or Muddy Waters record, the songs are crafted with a surprising level of sophistication, musical diversity, and memorable quality.

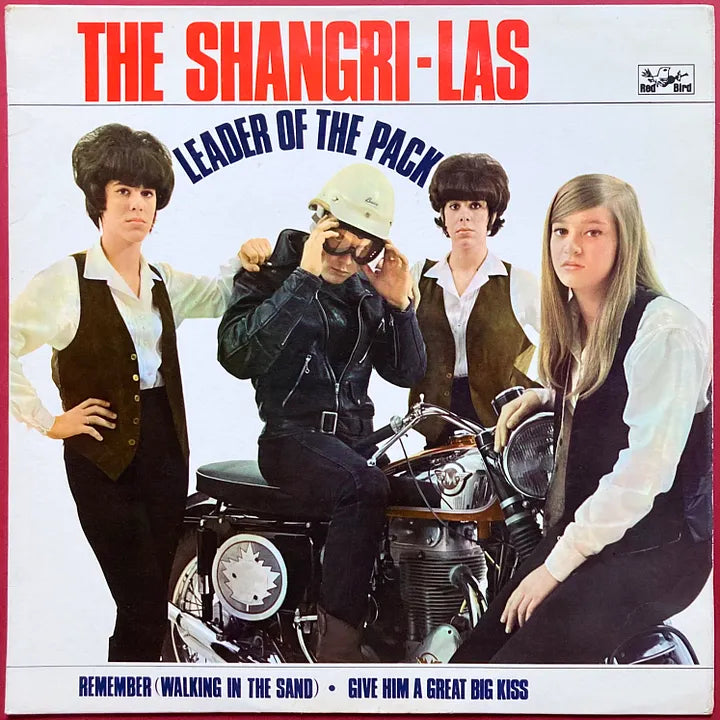

“Anyone Who Had a Heart” and “Walk On By” helped launch Dion Warwick’s and songwriters Burt Bacharach and Hal David's careers, and of course, “Be My Little Baby” is a work of pop perfection from Ronnie and Phil Spector. Even teenage tragedy “splatter platter” songs like the Shangla’s “Leader of the Pack,” goofy novelties like The Clovers' “Love Position #9,” or the Coasters' “Yakety Yak” are still fondly listened to today.

The superstar team of Lieber and Stoller penned over 50 rock and roll classics at the Brill Building, including "Hound Dog," "Jailhouse Rock," "Stand by Me," "Is That All There Is," "Kansas City," and so many more. A very short list of other notable Brill Building producers and songwriters includes Don Kirshner (yup, the “rock concert guy”), Neil Diamond, Sonny Bono, Carole King, Gerry Goffin, Neil Sedaka, Bobby Darin, Liza Minnelli, Donald Fagen, and Walter Becker (yup, Steely Dan), Frankie Valli & The Four Seasons, and the list is near endless.

Legacy

Music and business entities such as Motown, Muscle Shoals Studios, and Gold Star Studios, along with their in-house session players and producers, briefly extended the longevity of the professional musical collective. However, as technology progressed, musical styles and trends began to evolve faster, and the age of the centralized all-in-one music factory model began to wane.

Today, the U.S.A. is the primary source of popular music globally and an industry that generates over 17 billion in revenue annually. In this digitally connected world, asking “where” today’s music industry is located makes little sense, except to say that what was born on Tin Pan Alley came of age at the Brill Building. Today, the essence of Tin Pan Alley and Brill Building songwriting traditions has reached adulthood. From the “ABACAB” verse-and-chorus-based song structure, stylistic blending, and melodic structure paved the way for all popular music.

Blog posts

View all-

Alto Music Holiday Gift Guide 2025

The Holidays Are Here — and So Are the Best Deals of the Year The holiday season can get hectic—but there’s no need to let the “holiday crunch” become overwhelming. At...

Alto Music Holiday Gift Guide 2025

The Holidays Are Here — and So Are the Best Deals of the Year The holiday season can get hectic—but there’s no need to let the “holiday crunch” become overwhelming. At...

-

Blast From the Past: 50 Years of "Wish You Were...

With industry success to back it up, many Pink Floyd fans consider "Dark Side of the Moon" the "greatest album" ever made. With the same breath, the fans (and the...

Blast From the Past: 50 Years of "Wish You Were...

With industry success to back it up, many Pink Floyd fans consider "Dark Side of the Moon" the "greatest album" ever made. With the same breath, the fans (and the...